It’s only suiting that I pen my annual end-of-the-year editorial on the anniversary of my memorializing the passing of my father with an anecdote about him; namely, the day I received my driver’s license. I was about to leave out of my parent’s front door to go hang out with my friends when my father caught me in the doorway and offered a single line of council: “Don’t call me from jail and don’t come home in a body bag.”

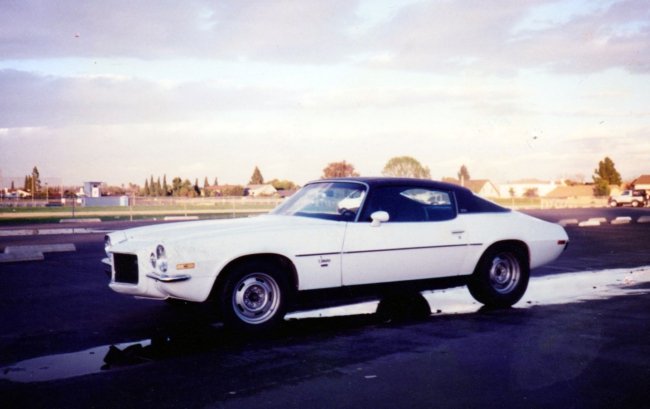

Albeit a curt and quite dark joke, the implication was clear: don’t be an idiot and be safe. I remember his wry smile as he gripped my shoulder. His youngest child now had a driver’s license and ergo, his first real taste of freedom. Ironically, I was an incredibly boring teenager, and apart from a single speeding ticket and a handful of very unsuccessful street races in my ’73 split-bumper Camaro LT, gave him little to worry about.

I recall sharing this moment with my older siblings who both reeled is protest. My brother and sister both recounted the “hour long lecture” they received before being allowed to drive off on their own. I countered their claims of favoritism and “getting off easy” with queries if either had given dad a reason to feel that such a lecture was necessary? I hadn’t. They had. Sometimes it pays to be the good kid, I smirked. That didn’t go over well, either.

This memory comes to mind as 1. my oldest daughter, Morgan goes in for her driver’s test in a few weeks (as of this writing) and 2. I observe a bit of a rift in our hobby. First, I’ve never foisted my interests or hobbies onto my three daughters. They have always been welcome to join me in the garage or on one adventure or the other, but I never made it mandatory with them. I didn’t think forcing my kids to like one thing or another would go well in my direction.

I suspect this is why I was so eager to return to Hot Rod Power Tour this past summer. Morgan surprised my wife and I when she expressed interest in going – although she was more enthusiastic to attempt the drive in our 1970 Plymouth Fury III convertible, which at the time, was far from being complete, or in the least bit, roadworthy enough to endure the trek. Rather, we climbed inside of the Charger and had a good time nevertheless.

It’s not often that a teenage girl volunteers to spend 7 solid days in a stripped-down, 56-year-old hot rod with no air conditioning or radio, strapped in next to her dad to go gallivanting from one asphalt lot to another with a bunch of strange guys in the middle of summer. But, as stated, we managed to have a lot of fun, see some pretty cool places, and have ourselves enough of an adventure that she’s asked to go again along with her 12-year-old sister.

Of course, this summer we’ll be piloting Project Marsha, our aforementioned Fury convertible. Power Tour’s June deadline gives me plenty of time to work out the bugs, tighten up the suspension and really dial-in the tune; so it’s a very attainable goal. Plus, C-bodies don’t get the credit they deserve as being a viable platform for entry-level enthusiasts, so it’ll be good to take Marsha out and demonstrate what a great build C-bodies make.

And while I won’t be submitting my name for any father-of-the-year awards, I will contend that this has been the best route for luring kids into this hobby (from what I’ve experienced). All three of my girls are continually surprised by random strangers approaching me, wanting to ask about whatever car I’m driving. The attention these cars draw tends to force one into becoming an extrovert. More importantly, the more events they attend and cars they see, the more they can observe where I put added effort where others don’t. That part is key: effort.

Too many “content creators” peddle trash – but can you blame them? YouTube’s fickle algorithm has come to reward many with fame who repeatedly seek out the most clapped-out $#%& boxes feasible, hose half a can of brake cleaner down its throat and coax a cough and sputter from its engine. Often these all-too-formulaic videos entail limping said rattletrap home and stowing it behind a barn until it either re-emerges in a second video to fix all of the “repairs” made in the first, or as a listing on Facebook Marketplace with a newfound premium price.

As a career “magazine man,” I find this degree of content not merely of the lowest tier but ultimately, damaging in the long term. Few of these creators who’ve cut their teeth on “revivals” have gone on to demonstrate a higher degree of mechanical prowess. It’s rare when Vice Grip Garage’s Derek Bieri breaks from his norm to assemble a high-output engine or Junkyard Digs’ Kevin Brown details proper carburetor tuning techniques – but I applaud them when they do.

See, we’re in a curious situation when it comes to education. We’ve never had such a population of newcomers with no prior experience or know-how. Equally, never before has there been such a glut of information accessible to the budding enthusiast.

YouTube, AI-assisted search engines, forums, and social media groups all offer immediate and satisfactory answers to any neophyte’s question. My concern is less if the answer given is factually correct but whether it’s directing them down the right path.

Many personalities within our hobby gain notoriety by appealing to our “lesser angels”; ie. plain old human laziness. Channels promoting slapdash repairs, using inferior materials or generally cutting corners encourage newcomers to take similar shortcuts that will ultimately need to be completely undone and repaired properly by somebody else down the road.

While humorous and certainly entertaining, screwing license plates to floorboards; packing rust holes with expanding foam before being slathered over in body filler; and twisting together a dashboard harness with wire nut connectors are more common “fixes” than should ever be considered. The whole “don’t get it right, just get it running” maxim appeals to our lowest interests and ought to be applied with strict moderation, if not rejected completely.

Without exposure to this segment of car culture, what my kids have been able to observe is how much of building a reliable, trouble-free car requires countless hours of hard work and discipline. Thankfully, cleaning up a sloppy engine harness or tightening up dangling fuel lines costs nothing more than some electrical tape and a few zip ties – that is, and a little extra time and effort. And there’s nothing saying a project in primer can’t have uniform panel gaps or aligned windows.

Back in my nascent days at Mopar Muscle Magazine, I was ardently opposed to Randy Bolig’s ’67 Plymouth Valiant because I felt there was nothing “cool” about a Valiant. What I missed was the sentiment Randy had towards the car, and more importantly, the degree to which he was building the A-body. Every inch of the car was immaculate. No corner was untouched. It took me years to learn that it was less about what kind of car he was building but how he built it.

In this light, I find best tactic is to lead by doing. Just like introducing my girls to classic muscle cars, or proving that a C-body is a very cool and affordable platform to build, it’s been my mission to illustrate ways to customize your project car; or get it back up and running without breaking the bank, requiring a two-post lift, or paying some shop to build it for them. When you distill it down, there’s just nothing else like driving a car you built yourself, except maybe sharing it with friends, family and fellow car lovers – and I’m all about helping Mopar enthusiasts to experience that same feeling.

– Kevin