For much of the twentieth century, Chrysler did something that puzzled mechanics, angered tire shop owners, and eventually became a defining piece of Mopar folklore. On the driver’s side of many Chrysler-built vehicles, the wheel studs were not right-hand threaded at all.

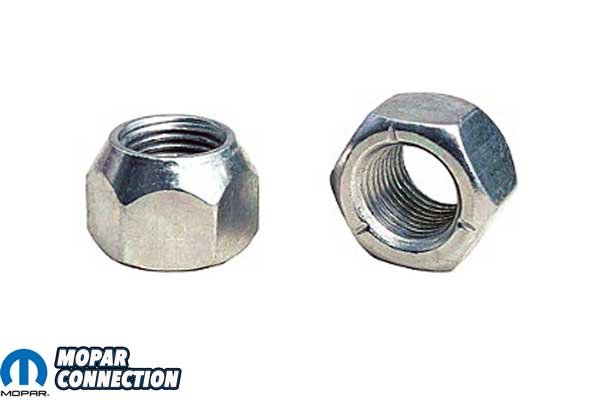

Above Left: Many unsuspecting weekend warriors and seasoned mechanics were caught by the dreaded left-hand threads. The result was broken wheel studs. (photographer unknown) Above Right: The technology of the day, which included lug nuts with no or minimal taper, thinner steel wheel construction, and soft lug studs, resulted in the right-hand threads on the driver’s side having a chance of loosening when the vehicle traveled down the road. The left-hand threads were introduced on the driver’s side of Mopars in the 1930s to eliminate the odds of the nuts loosening.

They were left-hand-threaded, a calculated engineering resolution decision rooted in early wheel design, rotational physics, and a period when keeping a wheel on the car was not as straightforward as it is today.

The reasoning centered on wheel rotation and the fear of rotational loosening. Early steel wheels, flat or lightly tapered lug nuts, and relatively soft studs did not provide the clamping force that modern fasteners do. Chrysler engineers observed that the driver’s side wheels rotate counterclockwise when viewed from the outside, and they believed that this rotation could encourage conventional right-hand threaded lug nuts to slowly back off.

Above Left: These early 1930s lug nuts lacked a deep taper, which helps hold the wheel in place. Due to loosened lug nuts, Chrysler reversed the thread direction. That prevented the lug nuts from backing off during driving. Above Right: Although a better taper design was used by the 1950s, Chrysler took no chances in having the lugs come loose. They continued the left-hand thread usage until the 1970s.

By reversing the thread direction on the driver’s side, the rotational forces acting on the wheel would theoretically work to tighten the lug nuts rather than loosen them. The passenger side, which turns in the opposite direction, retained conventional right-hand threads. It was an uncomplicated, symmetrical resolution that made sense in the context of 1930s engineering.

Chrysler was not alone in thinking this way. Several manufacturers experimented with left-hand threads during the same time. What made Chrysler unique was its long-term dedication to the idea. Beginning in the early 1930s, left-hand threaded studs became standard across most Chrysler Corporation brands, including Chrysler, Dodge, Plymouth, DeSoto, and Imperial.

The left-hand studs remained in place through the flathead era, the rise of the early Hemi, and well into the muscle car years. For decades, a Chrysler product implied reverse threads on the driver’s side, no exception.

To reduce confusion, Chrysler attempted to identify the hardware clearly. Left-hand lug studs were usually stamped with an “L,” and many lug nuts were marked with notches or hash marks on the top sides. Service manuals continually cautioned technicians to review thread direction before operating an impact gun.

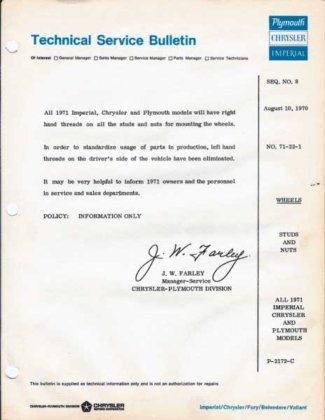

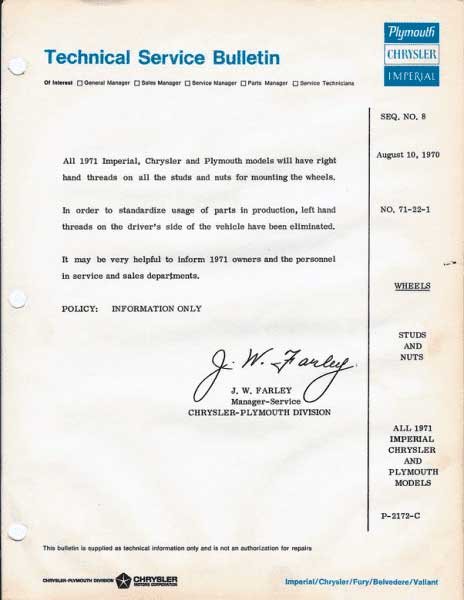

The end of the left-hand-threaded wheel-stud era came quietly but decisively. The technique was phased out during the 1970-71 model year for passenger cars, and by 1972 Chrysler had fully adopted right-hand threads at all four corners (with rare exceptions). A few heavy-duty trucks and specialized fleet vehicles carried the design slightly longer, but for consumer cars, the era was over.

The motivations were both technical and practical. Wheel and fastener configuration had improved dramatically by the late 1960s. Tapered-seat lug nuts, stronger studs, and higher torque specifications provided acceptable clamping force to prevent loosening regardless of rotation direction.

Above Left: Some aftermarket lug nuts (and even some factory lug nuts) came with three hashmarks to identify the left-hand threads. Above Right: If the lug nuts were not labeled with hashmarks, they may have been stamped with the letter “L.”

At the same time, the automotive service world was changing. Vehicles were increasingly serviced outside dealerships, tire shops relied on speed and standardization, and a reversed fastener became a drawback rather than a feature. Impact wrenches snapped studs, roadside tire changes went wrong, and a system originally intended to improve safety became a drawback.

Cost and coordination also played a role. Retaining two different stud size configurations and the matching nut inventories added intricacy to manufacturing and service parts distribution. As Chrysler entered the 1970s under financial pressure, undue variation was eliminated wherever possible. Engineering culture was shifting as well, moving away from legacy explanations and toward industry-wide conformity and ease of service.

Above Left: The left-hand threads were marked with an “L” stamping on the end of the stud. On the B-, C-, and E-bodies, the studs were 1/2-20, and the bolt pattern was 5×4.5 inches. Above Right: The smaller A-bodies had 7/16-20 studs with a 5×4-inch bolt pattern.

Today, Chrysler’s left-hand-threaded wheel studs occupy a quirky niche in automotive history. To restorers, they are a mark of genuineness, a detail that divides a correct car from a merely nice one. To racers and street drivers, they are often superseded by modern right-hand studs for convenience and consistency. To anyone who has ever snapped one off by turning the wrong direction, they are memorable.

Above: The replacement front drums for our ’67 Dart came with the traditional right-hand threads as noted by the lack of the “L” on the end of the studs. If we had desired the reverse threads, we would have had to press out the right-hand threaded studs and install the left-hand studs. However, like most enthusiasts, it was more convenient to keep the right-hand threads and convert the left rear over as well.

What matters most is understanding that the design was never a gimmick or a mistake. It was a brilliant response to fundamental limitations in early wheel technology, one that outlived its purpose. As materials improved and standards unified, the logic behind reverse threads faded away. What remains is a uniquely Chrysler solution, and a reminder that even the most frustrating design choices often began with sound engineering intent.

If your Mopar needs new lug nuts including left-hand threads, Year One has multiple offerings in 7/16-inch for A-bodies and ½-inch for B-, C-, and E-bodies.