Camshaft selection is about the most important part of an engine build. Unfortunately, when builders get it wrong, it’s almost always because of over-camming (a cam that’s too big) instead of under-camming.

Camshaft selection is about the most important part of an engine build. Unfortunately, when builders get it wrong, it’s almost always because of over-camming (a cam that’s too big) instead of under-camming.

For several decades, a friend’s 1970 Plymouth Road Runner was a strong driver with power aplenty from its 383 big block. It had factory high performance exhaust manifolds, factory cast iron 906 heads, and even the factory cast iron intake manifold. The only deviation from stock was a super mild “RV” cam from the early ‘90s, but this bird was a solid flyer.

However, in preparation for some long haul drives this summer, some well-meaning and ill-informed friends talked him into dumping a ton of money into it for supposedly more power and fun. On went an aluminum intake, headers, and alternative camshaft. Out went several thousand dollars. And when he got it back…it was an absolute slug.

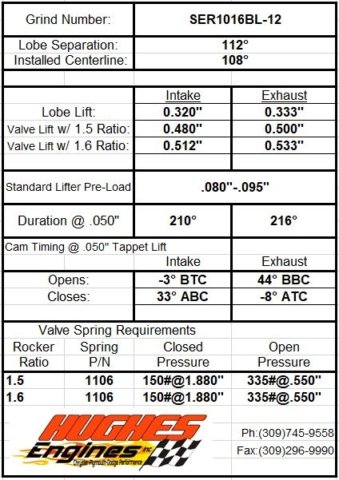

We went straight to the cam card and were unsurprised to find that some Joe Shadetree had installed a stick that was way too big. Durations at 0.050” of 238 degrees on the intake and 246 degrees on the exhaust were spec’d, way too much for such a basic 383 and no doubt the reason it had turned in to such a dog.

The list of suppliers we trust to pick a cam for vintage Chrysler wedges is exactly one company long: Hughes Engines. Their experts recommended something with about 30 degrees less duration to make “lots of low end torque for [the] street.” A much more appropriate grind (P/N SEH1016BL-12) with 210 and 216 degrees of duration will be in the mail soon and we’re 100% confident it’ll mend this bird’s wings.