Dodge stormed in to 1994 with a brand-new truck and defiant new slogan of “The Rules Have Changed.” Those “rules” were based on decades of trucks that were built to be workhorses without much thought given to comfort, convenience, or glamour. The message was that a heavy-duty truck didn’t have to be a boxy, boring shape with a rough suspension, poor handling, and spartan interior. With a “have your cake and eat it to” mentality, the Dodge designers put together a package that took its cues from cars of the era while still maintaining all the expected functionality of a truck.

The styling was revolutionary. Compared to the rigid, squared-off noses of its competitors, Ram’s new rounded hood draped over the engine bay and met its shapely fenders along the side of the body rather than on top. Because of that styling, it crushed the other full-size trucks in aerodynamics which also helped minimize noise and vibration in the cab.

The new “second generation” Ram also featured a number of safety elements and amenities that were formerly reserved for cars. Standard equipment included rear-wheel anti-lock brakes, a driver’s side airbag, and the most interior room for any full-size cab. It was the first full-size pickup to offer four-wheel anti-lock brakes and the only one to come equipped with an office-ready center console along with a behind-the-seat storage system that included modular trays, bins, and cargo netting. Much like the Plymouth GTX was the “gentleman’s muscle car” in 1970, the 1994 Ram was a construction worker in a tuxedo.

Above: Our 1999 Ram was long overdue for a steering solution.

Above: Fresh out of the box, Borgeson’s steering shaft was beefy and built right.

After taking home Motor Trend’s 1994 Truck of the Year, Ram sales exploded through the mid-‘90s. The groundbreaking design was so successful that it stuck around until 2002 as the complete lineup of Magnum engines plus the Cummins dutifully powered a great many of these trucks well into the 200,000+ mileage range. With most having surpassed the two-decades-old mark, second generation Rams have become well-known for three main things: rock-solid reliability, cracked dashes, and worn-out steering.

Our 1999 Dodge Ram 2500 recently finished checking off all three boxes: 198,000 miles are on the clock, the cracked dash has already been replaced, and now the steering has started to stray. Unfortunately, poor steering performance isn’t always remedied with an onslaught of replacement parts. In fact, that approach often doesn’t end up solving the problem since steering quality is so dependent on a host of other factors. The track bar, steering box, steering shaft, drag link, tie rods, ball joints, tire size, tire manufacturer, tire condition, and front end alignment all play a role in running straight down the road.

We found that it was best to start on the outside and work our way in. Tires, ball joints, and tie rods were all confirmed to be in proper working order. Next up was the track bar. Its purpose is to keep the axle in the correct location in relation to the frame. One end attaches to the solid front axle while the other generally mounts to a dedicated frame bracket. Verification of condition was gauged by carefully prying at each end and watching for undue movement. Ours was suspect and, therefore, replaced with Moog’s heavy-duty version (P/N DS1413).

Above: Each end featured heavy-duty U-joints. The steering box side was splined while the column side was sized with the appropriate double-D shape.

Continuing inward, the original steering box was the next shady character with our trusty prybar revealing a severely worn lower bearing. A rebuilt factory box was easy enough to source from the local parts store even though there are aftermarket options aplenty online. The last link was the steering shaft, a coupler between the box and the column that holds connection between driver and road. Simple as it may seem, it’s a surprisingly intricate series of shafts and joints.

From the factory, the upper portion attaches to the column’s double-D shaft via a pinch U-joint, followed by what is commonly known as a “rag joint.” The “rag joint” is actually a riveted assembly of rubber and steel that acts as a damper for any kind of road or suspension vibration. It’s connected to the male portion of a telescoping shaft who’s joint is covered by an accordion boot. The female end of the shaft runs down to another U-joint that mates to the steering box with a splined, single-bolt pinch connector. In factory form, it’s a decent unit that keeps everything between the ditches. But we weren’t looking for a decent replacement.

What we wanted was bulletproof and that meant a call to Borgeson. With a history in universal joints that dates back to the early 1900s, Borgeson has come to be known as one of the premier steering component suppliers for the street rod, muscle car, and truck industries. Several leaps forward in the 21st century accelerated their already successful path.

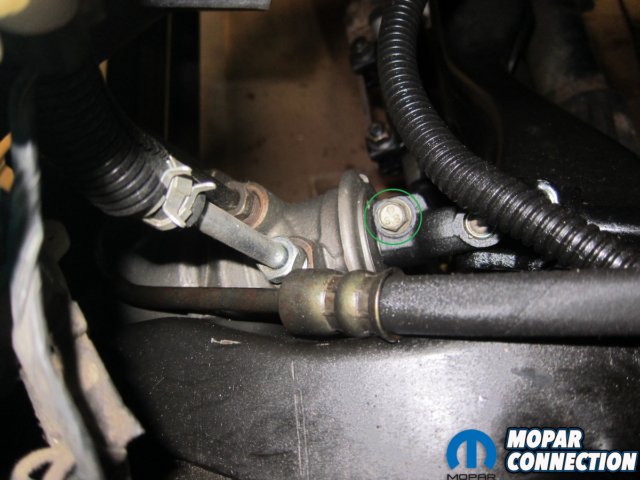

Above: The factory shaft’s steering box (left) and column (right) ends both incorporated a single-bolt (circled in green) pinch attachment.

Above: From above, the steering box bolt was barely visible under the power steering pump belt. The rag joint rested under the master cylinder. Lying underneath, there looked to be ample clearance for shaft removal.

Mullins Steering Gears was acquired in 2001 and served as Borgeson’s first big step into a wide range of steering offerings. Then, in 2012, they procured the OE manufacturing rights for Saginaw manual steering boxes, which included the original equipment, tooling, and blueprints. Finally, 2016 marked the move to a new, 101,000 square-foot facility in Travelers Rest, South Carolina.

All the while, business has been booming and support has stretched well outside the street rod sphere and into the stock replacement realm. Just like Dodge “changed the rules” on trucks, Borgeson has been changing the rules on quality steering for decades now. That’s exactly what led us to their heavy-duty 1995-2002 Dodge full-size truck steering shaft (P/N 000950). While it may seem like a simple enough assembly, the rigidity and heft of Borgeson’s unit was immediately noticeable when compared to the stock piece.

Replacing the flimsy rag joint on the column side was Borgeson’s solid steel U-joint. Not only were the yokes themselves meatier, but the elimination of the rag relinquished any of the slop we’d seen before. Opposite that was another solid steel joint, this one equipped with an integrated vibration reducer to handle the shocks and strains of everyday driving. Again, the yokes on the steering box side looked to be bigger and better, even to our untrained eyes. The ol’ bicep curl test confirmed that, at the very least, Borgeson’s shaft had some serious hulk to it.

Above: Side-by-side with the stock shaft, the Borgeson’s robustness was obvious at both ends.

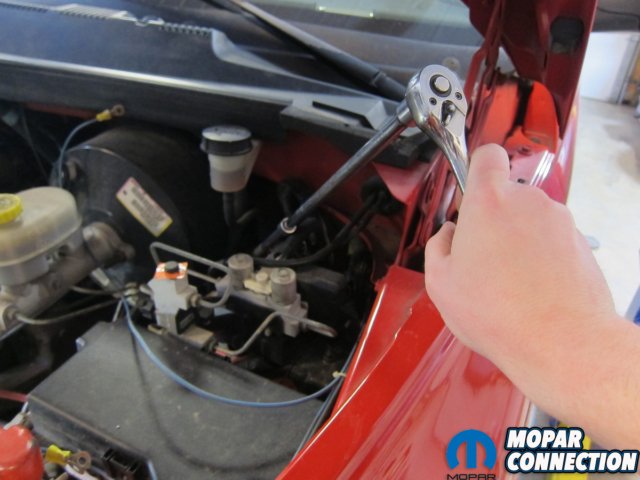

Above: The steering wheel was held in place with a bungee cord and the column lock while some long extensions took care of the pinch bolts.

Like any good manufacturer, Borgeson supplied detailed yet concise instructions that we followed to a tee. Locking the steering wheel was an important first step. After the wheels were centered, the ignition switch was engaged to keep the steering wheel from moving. We added an extra layer of hold with a bungee strap. Many don’t know that if the steering wheel is moved while the column is uncoupled from the steering shaft, the air bag clockspring will break. That’s an expensive little device that requires air bag removal for replacement, so we were sure to never touch the wheel once the shaft was removed.

Leaning in under-hood, a ratchet was equipped with 24-inches’ worth of extension to make removing the two pinch bolts a breeze. Lucky for us, both were pointing up and easily reached with our stretched-out socket. With them fully removed, the upper end of the shaft was collapsed and laid to rest on the frame rail. The steering box side was decoupled from underneath and the assembly slid out from below. Installing the Borgeson unit involved a similar process, but in reverse order. Of course, all set screws were removed first. Starting from the bottom, the fully-collapsed shaft was snaked upward so the lower joint could slide on the steering box splines. Up top, the double-D end fit snug on the column shaft.

One big difference of the Borgeson unit is that it uses set screws and lock nuts to hold U-joint position as opposed to the factory’s pinch clamps. Because of that, the set screws need to have a flat “seat” on which to tighten down upon. For whatever reason, the rebuilt box we installed already had multiple flat spots on the splines, one of which aligned perfectly with the new U-joint. If that wouldn’t have been the case, we would have tightened the set screw to mark the splines, then ground our own flat in the appropriate location.

Above: On the steering box side, the set screw was tightened down on its matching flat. While underneath, we slid the upper end of the shaft under the master cylinder and up towards the column.

Above left: With the set screws removed, we had access to mark and drill dimples for seating on the column. Above right: The final piece of the puzzle was the additional safety collar which butted up against the protective boot.

The opposite end was similar but, since it’s a double-D connection instead of splines, the pair of upper set screws just needed corresponding dimples on which to properly seat. With the shaft in place and the set screws removed, we were able to squeeze a small drill under the master cylinder to create these dimples. Both ends of the shaft were fully prepped at this point, so the set screws were installed and locked down with the supplied nuts.

The last step was to position a steel stop collar on the lower telescoping shaft. Similar to what Chrysler did as part of an added safety feature in early trucks, this collar is meant to prevent full disengagement of the steering shaft in the event of a component failure. We slid it up to the bottom of the boot and tightened the final screw.

Confident the truck would be more surefire on the street, we whipped out of the shop and onto the road. Right away, it was clear that both low and high-speed maneuvering were much improved. The beef of Borgeson’s steering stick improved both responsiveness and shock absorption at every level. At cruising speed, the wheel no longer required a two-handed wrestling match for every jounce or jolt. One hand on the wheel and one hand on the shifter, we’re ready for the next fork in the road for our Ram.

Mopar Connection Magazine – The ONLY Daily Mopar Magazine © 2022. All Rights Reserved. Mopar Connection Magazine is the ONLY daily Mopar Magazine bringing you the latest Mopar news, technology, breaking news, and Mopar related events and articles. Find out the latest information about Mopar, Mopar products and services, stay up to date on Mopar enthusiast news, dealership information and the latest Mopar social media buzz! Sign up for the Mopar Connection Magazine newsletter for the latest information about new products, services and industry chatter. Mopar Connection Magazine is the best and only source you need to be a Mopar industry insider!

Mopar Connection Magazine – The ONLY Daily Mopar Magazine © 2022. All Rights Reserved. Mopar Connection Magazine is the ONLY daily Mopar Magazine bringing you the latest Mopar news, technology, breaking news, and Mopar related events and articles. Find out the latest information about Mopar, Mopar products and services, stay up to date on Mopar enthusiast news, dealership information and the latest Mopar social media buzz! Sign up for the Mopar Connection Magazine newsletter for the latest information about new products, services and industry chatter. Mopar Connection Magazine is the best and only source you need to be a Mopar industry insider! by

by