Time has taught some old dogs plenty of new tricks. Advanced technologies have increased efficiencies, pushed capacities and reduced effort and waste in ways many couldn’t have predicted even a quarter-century ago. Strides in metallurgy, computer modeling and resource management have not only increased the speed, efficacy and cost of manufacturing, but permitted the growth of specialized facilities and foundries, capable of operating under manageable overhead costs, producing short or small quantity production runs. It was at one such operation, the Muncie Casting Corporation, that we were entreated with a firsthand demonstration how a modern Bulldog Performance wedge/Hemi block is designed, cast, poured and machined.

For those not following Mopar Connection Magazine closely, we announced a little over a month ago that Bulldog Performance – the original developer of the iron wedge/Hemi engine block that was sold through Muscle Motors – is continuing to produce its NHRA-approved (for Stock and S/SC classes) ultimate cast iron wedge/Hemi engine block. Helmed by famed engine builder, and engine block and cylinder head designer, Dick Bradshaw, Bulldog Performance specializes in aftermarket performance parts that otherwise cannot be found elsewhere. A self-proclaimed “old hat” at Chryslers, Bradshaw’s versatile wedge/Hemi was birthed out of necessity after the supply of suitable stock and replacement engine blocks dried up in the late 2000’s.

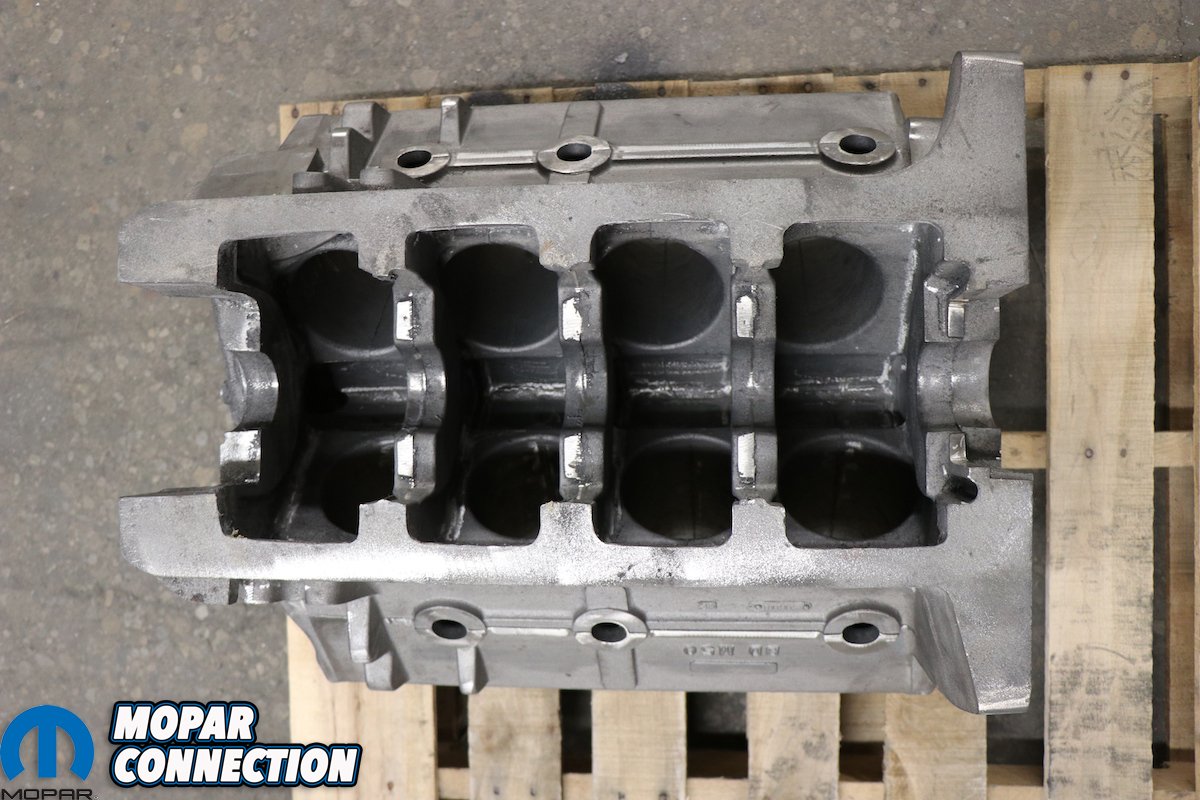

Top: Bulldog Performance’s Dick Bradshaw was eager to show us a prototype high-flow, NASCAR-inspired small block LA/Magnum cylinder head design he has been working on. Pulling a lot of inspiration from the W8 cylinder head, it’s expected to outflow most conventional G2 Hemis. Bottom: Using permanent molds, a cast casting is made for the Bulldog Performance Hemi engine block. What is shown are both ends of a single engine block mold that will be stacked together, secured and filled with molten iron.

This drought affected sportsman racers, owners of street machines and performance enthusiasts most, as racers competing in Super Stock, Super Comp, and other classes running big-block Mopars quickly gobbled up any available high performance Mopar big blocks. Mopar Performance’s own line of wedge and Hemi “Mega Blocks” during in the mid-1990s, were all but gone; Mopar’s Hemi blocks were suffering internal alignment/core shift issues; and aftermarket brands who offered engine blocks were either ridiculously back-ordered, or extraordinarily overpriced due to increasing demand. Per Bradshaw’s account, Bulldog’s block couldn’t hit the market soon enough.

Alas, Bradshaw wouldn’t let the engine block “loose” until it was “right,” he recalls. The new engine block featured stronger, thicker main webbing, each filled in for added strength. New larger and rerouted passages ensured priority oiling supplied the main and rod bearings prior to the lifters, ensuring lifter failure wouldn’t happen as a result of total loss of main bearing oil pressure. In its primary form, the block came at 4.495″ bore, with a .250″ wall thickness at 4.500″ bore. Made available with either 9.980″, 10.200″ or 10.720″ deck heights, meaning you could literally order a low deck 400, or a raised deck 440 Wedge or 426 Hemi. All you needed to do was check the right box when you made your order.

Above: Shown are a set of templates for the water jackets in Bulldog’s tall deck engine blocks, one being for 440 wedges, the other Hemis. These larger water jackets deviate from factory greatly, providing larger room for cooling and better flow management.

Above: Engine blocks are poured in short batches so that the team at Muncie Casting Corporation can carefully measure the unique metallurgy of each pour. Temperatures, mineral blends, and chemistry are each meticulously measured prior and after each casting to ensure that porosity, imperfections and contaminants are kept to a minimum.

Equally, the cam bore was machined either for a 55mm roller or 60mm slider. You even could decided to machine the block for either wedge or Hemi motor mounts (which makes needing to buy expensive Hemi-swap motor mounts or exchanging K-members obsolete). Additionally, four of the five steel billet main caps came cross bolted, and the entire block was fitted with with ARP fasteners. Lastly, Bulldog made all freeze plugs and seal retainers come included with each purchase. The Block hit the ground running, particularly as it was sold exclusively through Detroit engine builder Muscle Motors for a short time. Other vendors sprung up as well, with many unaware that the engine block itself was Bulldog’s.

With a bit of a rocky start and some early run teething issues to square up, Bradshaw partnered with Muncie Casting Corporation to handle the much needed foundry work. With a reliable template and team behind it, production of The Bulldog Block (albeit limited) began to pick up steam. First, Bulldog sought to satisfy its most patient customers, those who had been waiting after delayed responses to phone calls and emails from vendors and outlets either no longer in business or is cooperation with Bradshaw. Next, batches of newly minted blocks began arriving by the pallet load for final machining.

Above: Once the sand casting is fully prepared and the molten iron is at the desired temperature, the Muncie Casting Corporation team slowly lowers the vat, pouring a measured portion of the iron into a conveyor-mounted bucket. Safety is of the utmost importance here, and MCC has taken extreme measures to ensure that its team and facility meets the outlined regulations.

Above: Pouring the casting is dangerous work. The MCC team carefully fills the two-piece mold with molten iron. Massive blocks weigh down the mold as the heat and rapidly expanding and contracting metal can cause dangerous core shifting. If such misalignment happens, the block itself is worthless and needs to be destroyed, and cast again.

With the process now in full swing, Dick Bradshaw invited us up to Muncie, Indiana to personally witness the pouring of two iron blocks during a visit prior to the PRI Show in December 2018. We were greeted by Muncie Casting Corp.’s General Manager, Bob Buchert who also played tour guide for the two hours we were there. The facility specializes in top quality, durable aluminum and iron parts cast using sand, permanent and semi-permanent molds and dies; as well as full production and prototype-quantities of specialized products; and features state-of-the-art machining, tooling, and casting processes.

Buchert and Bradshaw shared a long history, as Bradshaw used Muncie Casting for much of his product development work while working for Indy Cylinder Heads many years earlier. Walking past the second set of double doors, we entered into the pattern-making room. This had all the feel of a high school woodshop, as the original dies and molds are first given life here. Bradshaw motioned to a large pair of boxes identifying them as the prototype designs for a new set of small block cylinder heads that borrow many characteristics from the Magnum and race-bred W8 cylinder head used by NASCAR. The mold itself was a stacked series of wood and plastic layers all creating an inside-out version of what a cylinder head should look like.

Above: Once cooled, the casting is vibrated and pressure washed to remove any trace of the sand-casted mold. What remains is a very unique look at the path the molten iron takes to fill the mold. These large amounts of “flash” are removed in one of several rounds of machining and preparation.

Above left: While the engine block is broken from its mold, the remaining molten iron is analyzed for impurities, and eventually smelted into slag for future pours. Above right: All excess material is preserved, sorted and used where possible to ensure the least amount of lost efficiency or excess material overhead.

Once finalized, these patterns are cast into dies that will be the templates from which sand-cast molds will be created. Buchert escorted us to the sand mold room, where a combination of silica sand, clay, and water are poured in to the one half of the pattern surrounded by a wood or metal frame. The sand-filled mold is then compacted inside of the machine by applying pressure to the metal frame. This process results in a hardened sand mold that looks like an inverted engine block, with all of the water jackets and oil passages floating in negative space inside the two halves of the mold, that is before molten iron is poured in and hardened. Large clamps and weighted blocks tighten the seal around the mold so the pressure of the molten metal won’t leech out. A single funnel-shaped port acts as the inlet for the glowing liquid that’s poured in.

The center hole in front fills the mold from bottom up to the top through the risers. The risers supply the necessary extra molten metal during the cooling process. As the metal cools shrinkage occurs, and thereby requires extra metal to fill the mold. This is satisfied by the risers by drawing the molten metal in the riser back down in to the casting. As we watched the blistering-orange metal pour into the casting, a small portion was poured into a second mold, no larger than a toaster. “This is for testing. We test the metallurgy of each pour for contaminants, impurities and different metal levels,” Buchert explained. Each freshly poured block takes at minimum 24 hours to cool before the compressed sand mold is broken apart by vibrating the casting. Then, the rough casting is washed to remove any residual sand before going to machining.

Above: After knocking off the larger bits of casting flash, each block is passed through a second round of machining to clean up the machine surfaces before going into for final machining. At this stage, you’ll note no holes have been drilled for lifters, distributor, the camshaft or oil passages.

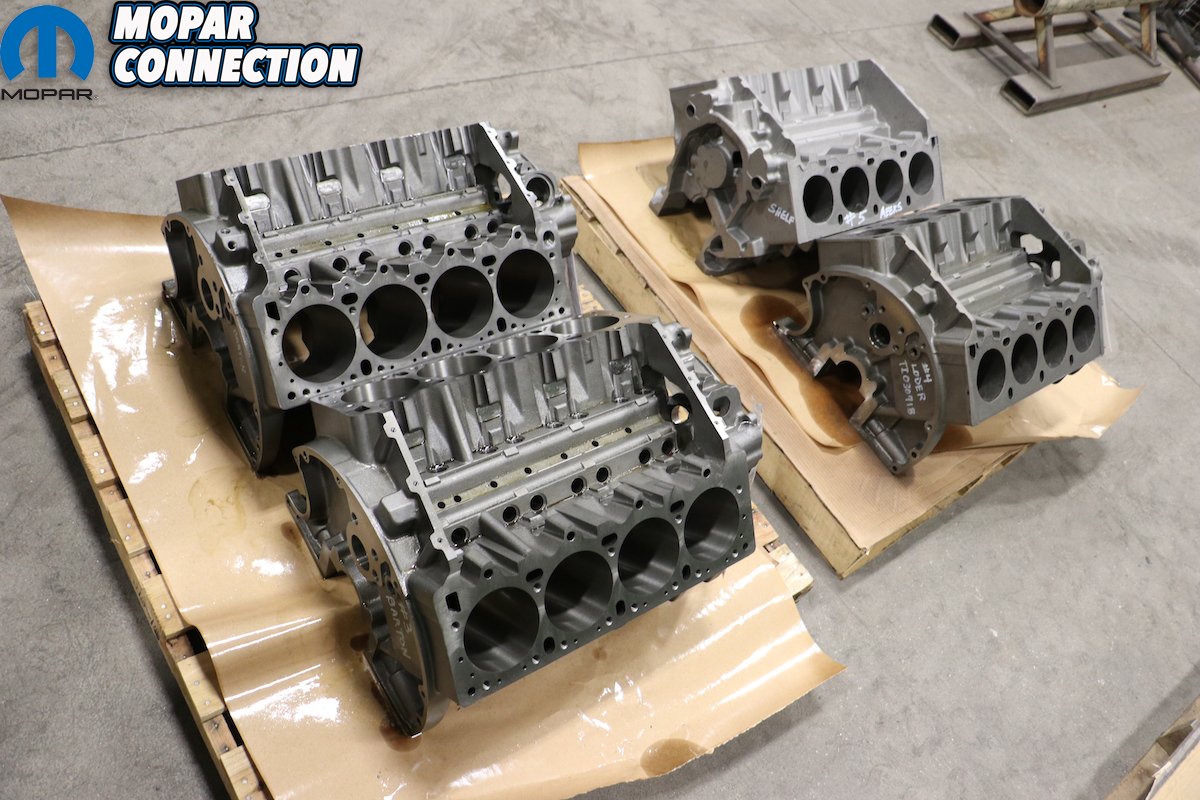

Above: These finalized engine blocks have been final machined to the customer’s exact specifications (except for one, left “rough” for a unique build – upper right hand corner). In this instance, the blocks were earmarked for a race team. Engine blocks are available for purchase or custom order by calling Bulldog Performance at 317-869-8689.

Each casting is given a “rough machining” to remove the large portions of casting flash, including the funnel where the molten iron was poured in. Next, the engine block passes through a second round of machining to get correct dimensions and smooth the more sensitive machine surfaces. This complicated process prepares the engine block for cylinder head surface machining, cylinder boring, and line boring the main bearings, among other sensitive areas. Temporary main caps are fitted, and the boring bar set up. It takes several cutting tools and passes of the bar to exact the right dimensions for the crank and the cam shaft bearing housings. Once complete, the crank and cam bearing journals are checked for clearances, whether per Bulldog’s specifications or those of the customer.

Offering its engine block in either low deck or raised deck configurations isn’t a matter of machining off the top, but requires its own unique sand casting. It’s mainly the internal specifications, wall thickness, proprietary oiling and bottom end structure that is shared between the 400, 440 wedge and the Hemi configurations. Priced typically at $3,975, each block is made to exacting customer specifications, so prices and delivery dates are understandably subject to change per order. Before leaving, Bradshaw pointed to a pair of pallets heading off for final machining off-site. “These are the latest batch to come out. Going to a couple of drag race teams. We had to hurry these blocks up so that they could be ready in time for the season.” So again, if you’re looking for a new iron Hemi block (or performance 400 or 440), they’re available for order at Bulldog Performance (give them a call at 317-869-8689).

Mopar Connection Magazine – The ONLY Daily Mopar Magazine © 2022. All Rights Reserved. Mopar Connection Magazine is the ONLY daily Mopar Magazine bringing you the latest Mopar news, technology, breaking news, and Mopar related events and articles. Find out the latest information about Mopar, Mopar products and services, stay up to date on Mopar enthusiast news, dealership information and the latest Mopar social media buzz! Sign up for the Mopar Connection Magazine newsletter for the latest information about new products, services and industry chatter. Mopar Connection Magazine is the best and only source you need to be a Mopar industry insider!

Mopar Connection Magazine – The ONLY Daily Mopar Magazine © 2022. All Rights Reserved. Mopar Connection Magazine is the ONLY daily Mopar Magazine bringing you the latest Mopar news, technology, breaking news, and Mopar related events and articles. Find out the latest information about Mopar, Mopar products and services, stay up to date on Mopar enthusiast news, dealership information and the latest Mopar social media buzz! Sign up for the Mopar Connection Magazine newsletter for the latest information about new products, services and industry chatter. Mopar Connection Magazine is the best and only source you need to be a Mopar industry insider! by

by