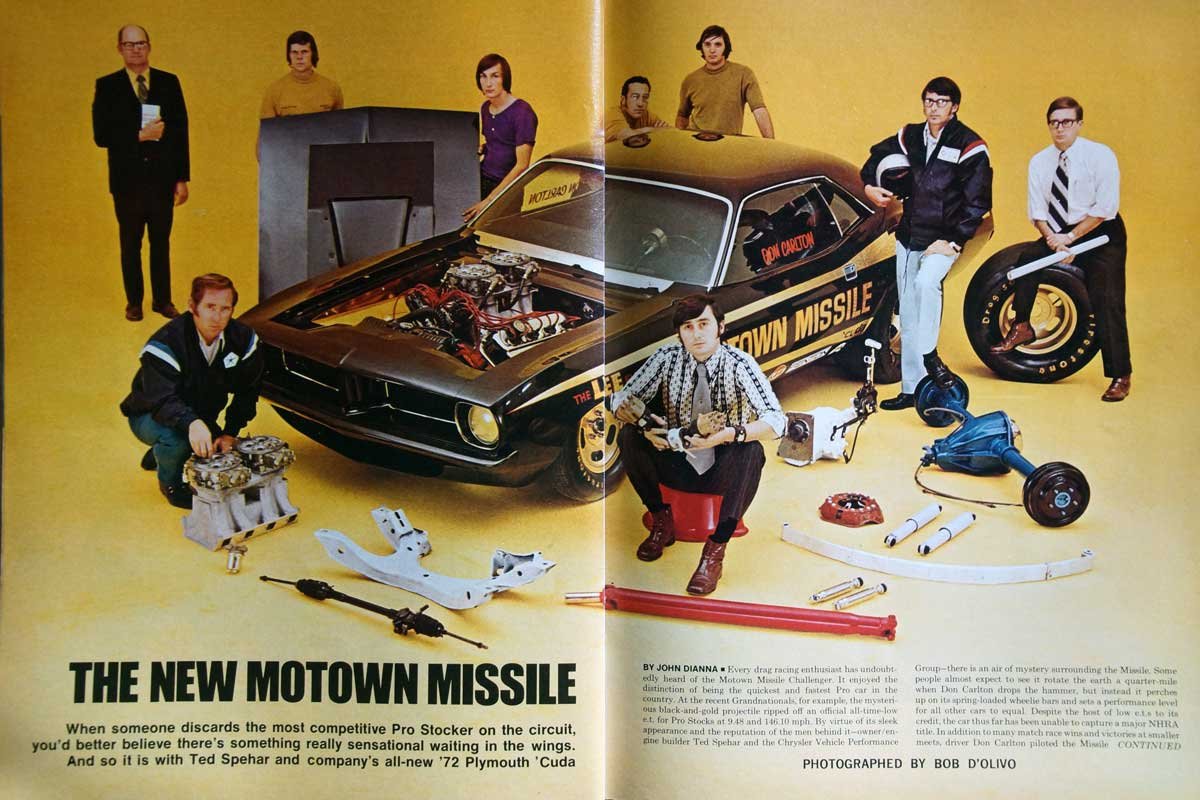

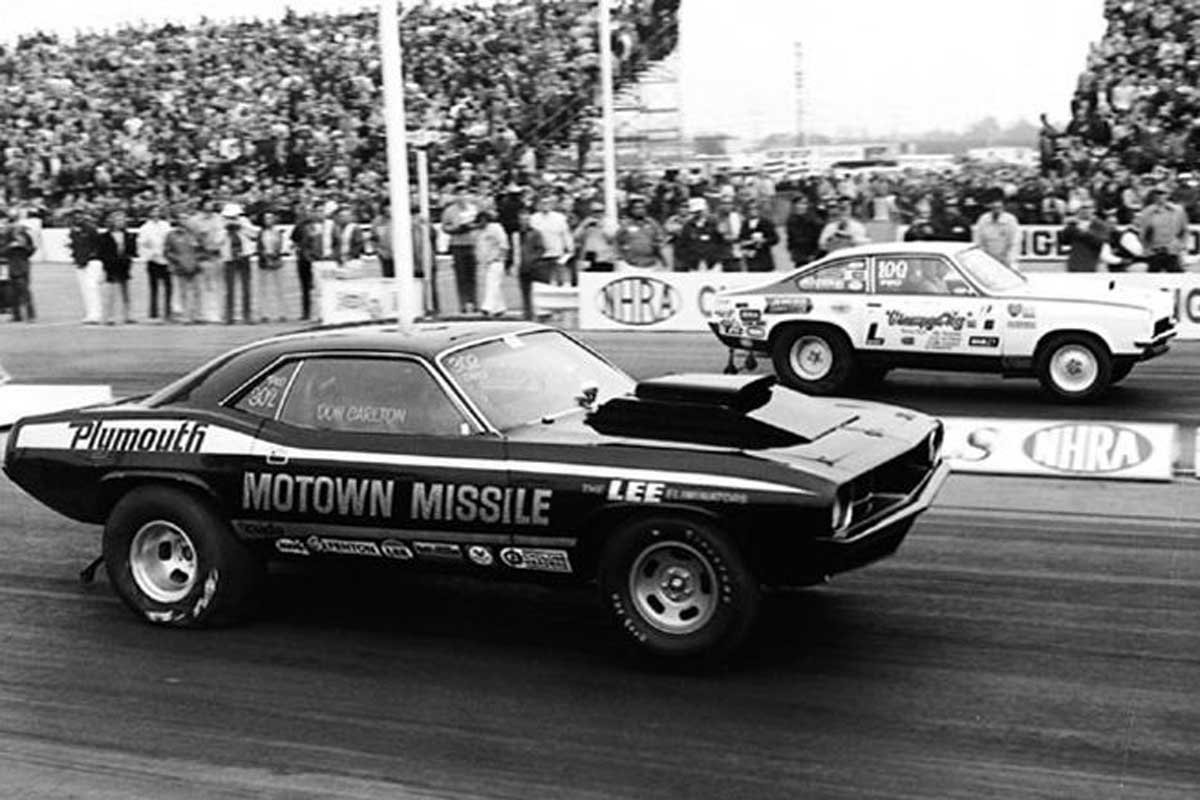

After running a 1970 (updated to a 1971) Dodge Challenger for the first two years of Pro Stock eliminator, the Motown Missile team upgraded to an all-new 1972 Plymouth ‘Cuda. Chrysler developed the Missile program as a factory testbed to evaluate components and test theories and pass the gained knowledge to the other Chrysler factory drag racing teams.

After running a 1970 (updated to a 1971) Dodge Challenger for the first two years of Pro Stock eliminator, the Motown Missile team upgraded to an all-new 1972 Plymouth ‘Cuda. Chrysler developed the Missile program as a factory testbed to evaluate components and test theories and pass the gained knowledge to the other Chrysler factory drag racing teams.

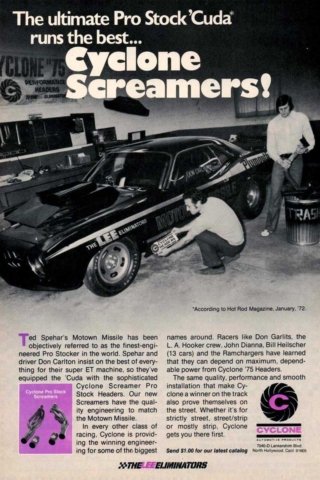

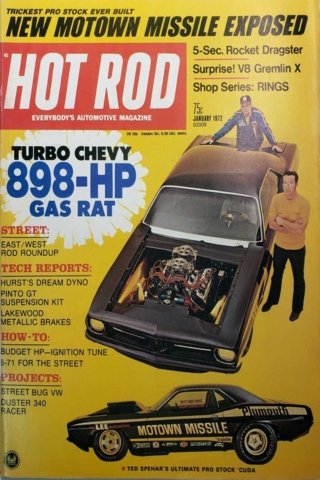

Above Left: The Motown Missile team added to Cyclone Headers for the 1972 season. The headers met the team’s high standards. The advertisement was featured in the October 1972 Super Stock & Drag Illustrated magazine. Above Right: The Motown Missile team earned the cover of the January 1972 Hot Rod magazine. A seven-page editorial covered the team’s advanced engineering to compete in the Pro Stock class.

The 1972 Missile team, which included Ted Spehar (car owner), Don Carlton (driver), Tom Hoover, Al Adam, John Baumann, Leonard Bartush, Tom Coddington, Mike Koran, and Dick Oldfield, built “the ultimate Pro Stock ‘Cuda,” according to a 1972 October Super Stock & Drag Illustrated magazine advertisement.

Ted Spehar’s peers considered his Missile cars the finest-engineered Pro Stockers in the class, and the ‘Cuda was no different. Spehar and his team demanded the best pieces for their Mopars. To that point, the team snaked a pair of 2 ¼-inch Cyclone Pro Stock Screamers (headers) into the engine bay to help scavenge the burnt hydrocarbons from the high-compression 426 Hemi. The advanced technology of the Cyclone headers matched the team’s high-standards reputation.

Above: The Motown Missile team poses next to their super-trick ‘Cuda. All the Motown Missile cars were designed as testbeds for the Chrysler Corporation. The team competed in NHRA, IHRA, and AHRA events, but the main focus was non-stop testing during the weekdays between each event. (Photo by Bob D’Olivo)

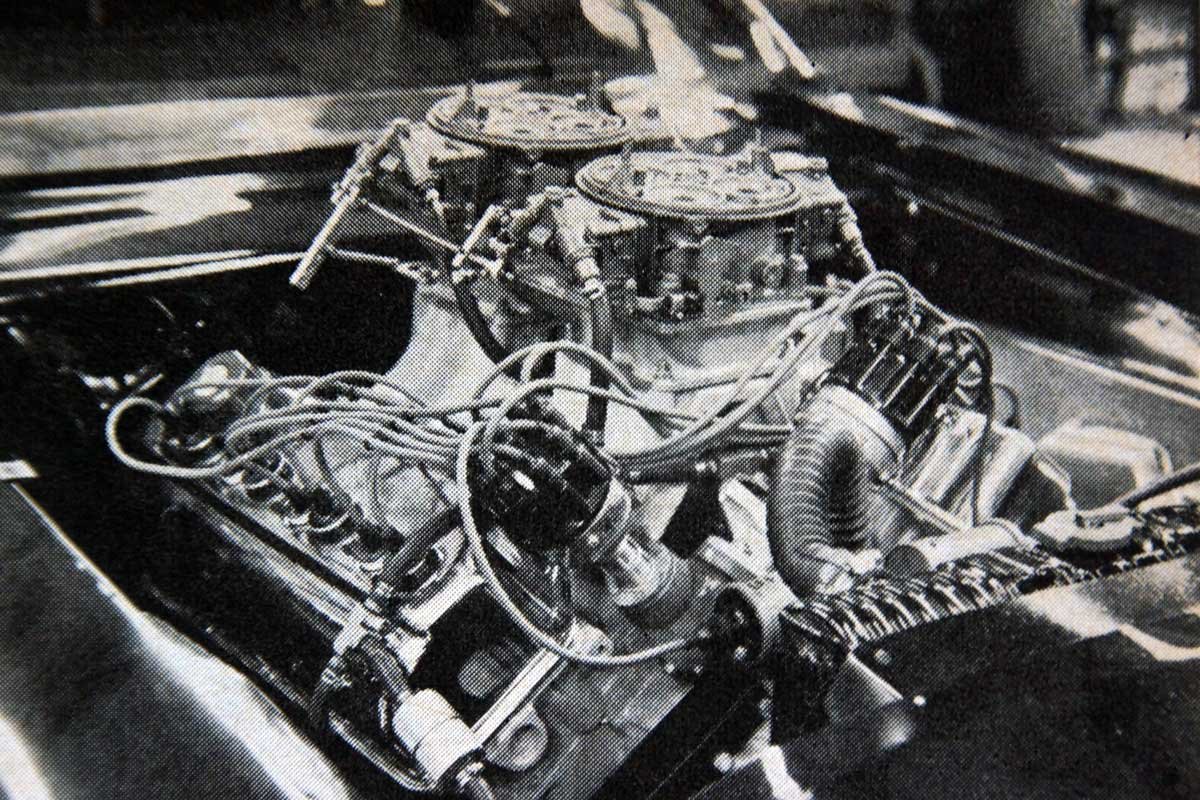

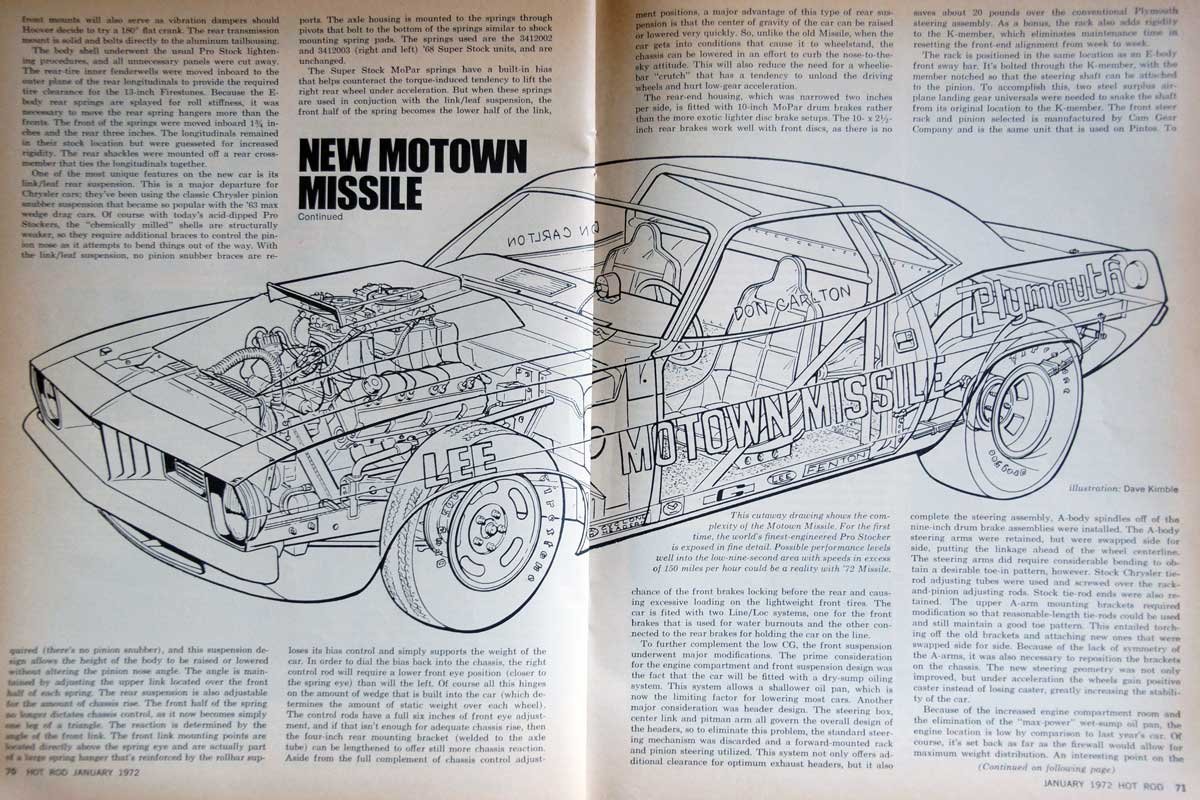

The 1972 ‘Cuda incorporated all the team had learned in the previous two years, with some new ideas added to make the car even more competitive. The suspension was a radical departure from stock. The most noticeable deviation was a rack-and-pinion steering gear attached to the front of the K-member. In addition, the team swapped the lower ball joints side-to-side to line up with the forward-mounted rack’s inner tie rods.

The removal of the factory recirculating ball steering box and related steering linkage reduced the frontal weight of the ‘Cuda by 20 pounds. With the quarter-mile speeds quickly approaching 150 mph, the team re-engineered the upper control arms. Furthermore, it installed A-body spindles to provide improved steering geometry and additional positive caster for vehicle stability at high speed.

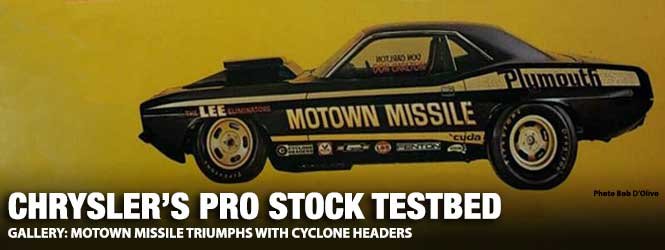

Above: The NHRA established weight breaks for the Pro Stock class in 1972. The Hemi cars had to carry nearly 900 more pounds than Bill Jenkins’s minicar with a 331-cubed mouse engine. The Hemis cars struggled, while Jenkins had a great year. (Photographer Unknown)

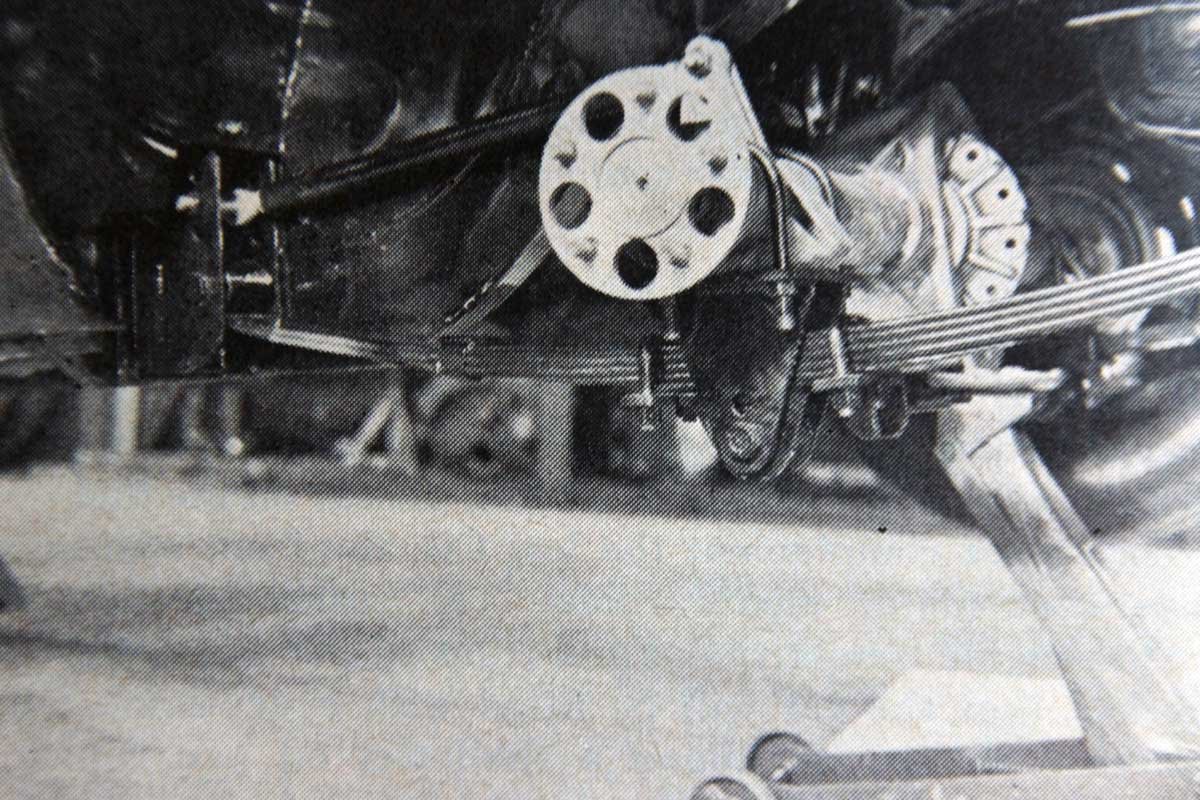

The rear suspension utilized a pair of Mopar Super Stock springs. However, they were teamed with upper tubular links that extended from an adjustable anchor at the spring hanger to brackets welded to the upper side of the rear axle. The suspension was known as a leaf-link design, which provided the adjustability of a four-link suspension while maintaining “factory” rear springs.

To lower the front of the ‘Cuda and achieve the desired 2° nose-down rake, the Missile team switched from a wet sump oiling system with a deep pan to a shallow oil pan and a dry sump system. Besides allowing a lower front-end height (lower center of gravity), the dry-sump system prevented oil starvation concerns, increased oil capacity, maintained better oil temperature control, reduced internal engine parasitic losses, and improved engine power.

Above: Chrysler developed a leaf-link rear suspension. The upper link (one on each side) allowed the team to adjust the suspension’s instant center to fine-tune the suspension for any track condition. (Photographer Dan Bartush)

Sadly, the cutting-edge ‘Cuda was quickly outdated and less effective than the previous Missles. However, it was not for lack of work by the team. Instead, the drag racing sanctioning bodies, especially the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA), changed the rules and added additional weight based on engine cubic inch displacement and cylinder head valve arrangement. The extra weight effectively slowed the Hemi cars down.

After dominating Pro Stock (and most racing classes) in 1970 and 1971, the Chevy and Ford faithful whined into the sympathetic ears of various NHRA officials. The weight just kept being added until the Hemis were ineffective. The pocket-sized Pro Stock car era (Vega, Maverick, Pinto) had begun.

Above: Dual plug heads were used on the Hemi. At the time, NHRA had a rule that the engine’s frontmost spark plug hole could not be further back than the front spindle centerline. The dual plug head, while performance-wise was minimally better than a single plug head, did allow a more significant setback, which was an advantage.

Above: Dual plug heads were used on the Hemi. At the time, NHRA had a rule that the engine’s frontmost spark plug hole could not be further back than the front spindle centerline. The dual plug head, while performance-wise was minimally better than a single plug head, did allow a more significant setback, which was an advantage.

While the effectiveness of the 1972 ‘Cuda was limited in NHRA, the Missile, again with Carlton driving, captured its 2nd International Hot Rod Association (IHRA) world championship in a row. In fact, between 1971-1973, Carlton and the Missile would be in the finals of sixteen of the first twenty-two IHRA national events, winning ten titles.

However, by the end of 1973, Chrysler moved its Pro Stock racers to other classes (Modified Production, Super Stock, and Gas class) in protest of the constant weight additions. After 1973, a competitive Chrysler Pro Stock vehicle would not be seen at an NHRA track for almost two decades, except for Bob Glidden’s 1979 season with his small-block Arrow, until the Wayne County Speed Shop sponsored “Dodges Boys” (Darrell Alderman and Scott Geoffrion) arrived on the scene in the early 1990s.

Above: The Motown Missile was delivered as a ‘Cuda in white. It was production chassis with plenty of modifications. Unfortunately, Bill Jenkins showed up at the NHRA Winternationals with a complete tube frame chassis, which made the new ‘Cuda out-of-date before it ever competed. (Illustration by Dave Kimble)

Cyclone Automotive Products started selling headers in the 1960s that were known for performance and dependability. Then, in the early 1970s, Cyclone began an ad campaign for its latest header designs. Known as the “Race into Tomorrow with Cyclone ’75 Performance Headers – Years Ahead of Their Time,” Cyclone was able to push the engineering envelope by developing quality headers during the infancy of the Federal emissions directives.

In 1993, Tenneco, Inc. purchased Performance Industries, which manufactured Cyclone and Blackjack header products and Thrush mufflers. The Thrush muffler is famous for its colorful woodpecker logo. Moreover, Walker, another Tenneco subsidiary, launched its renowned DynoMax Performance Exhaust product line in 1987. After the acquisition of Performance Industries, portions of the Cyclone, Blackjack, and Thrush exhaust products were inserted into the DynoMax catalog.

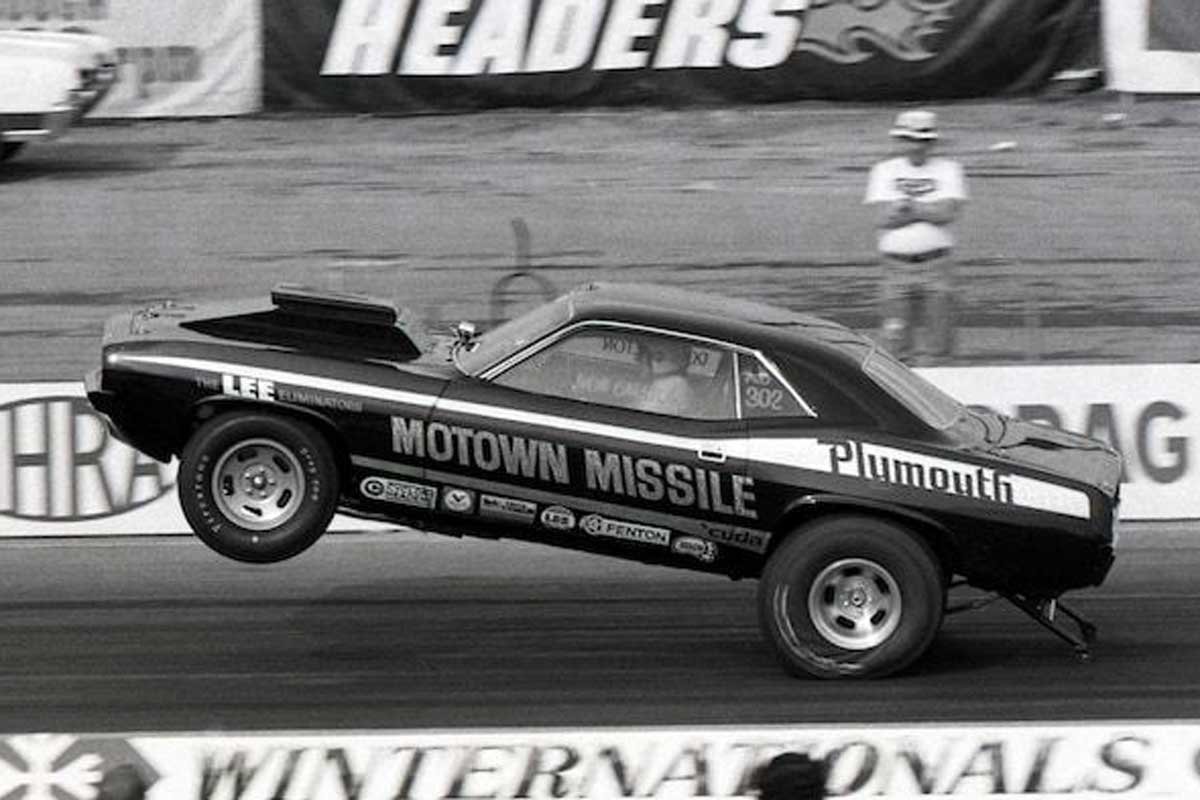

Above: A wheelie is not seen in modern Pro Stock, but in the early-1970s, it was a real crowd-pleaser. The wheel stands became problematic due to excessive pitch rotation. The Motown Missile team developed wheelie bars to control the wheelies without unloading the rear tires. (Photographer Dave Kommel)

By 1999, Tenneco separated its automotive division from the rest of its businesses. The new company was called Tenneco Automotive. The company reverted to the Tenneco name in 2005. The company thrived; it purchased many companies, including Federal-Mogul. Apollo Global Management acquired Tenneco in November 2022 for $7.1 billion.

Through all the years and name changes, Cyclone has continued to be a mainstay for excellent header performance at a moderate price. Today, each Cyclone header comes with a silver high-luster ceramic coating, emission fittings as needed, and all the mounting hardware, and each is 100% quality tested.

Above: Cyclone headers are now part of the DynoMax product line. The headers come with a luster coating and all the mounting hardware to install.

For more information about the 1972 Motown Missile, find a January 1972 copy of Hot Rod magazine with a seven-page spread on the ‘Cuda, penned by John Dianna. Additional information about the entire Missile program is packaged in Geoff Stunkard’s well-written book, Chrysler’s Motown Missile: Mopar’s Secret Engineering Program at the Dawn of Pro Stock. And lastly, check out Mancini Racing and Classic Industries for DynoMax exhaust products.